PAINTING THE MUSIC

Vladimir Tamari

MOZART (3)

|

November 19, 2004. I had not painted to music for a couple of years, nor even listened to much music for a very long time. A few weeks before I had discoved an Internet radio station[24] that broadcast only Mozart which suggested another 'Mozart painting'. Towards the end of a cool autumn day, when the foliage had turned deep mellow blend of poignant colors, I was in just such a mood. An elderly aunt had sent me a photograph showing my grandmother taken in her home in Jaffa in Palestine. Her home was the scene of my earliest memories in the mid-1940's. I put on the Mozart station and to the brilliant cheerful music of Mozart as a child and teenager, I painted the entire painting in one hour and twenty minutes. The swirling forms correspond to those of a couple of my earliest serious works. I had also been researching my physics theory[25] of a Universe made up of ether particles that transfer angular momentum by just rotating in place, so the swirling motion was very much in my mind. The music pieces (or excerpts from them) heard in order were: Violin Concerto Nos. 2,3,4, Piano Concerto No.2 in B flat, Symphony Nos. 22, 23. Piano Concerto No.4 and Symphony No.24. |

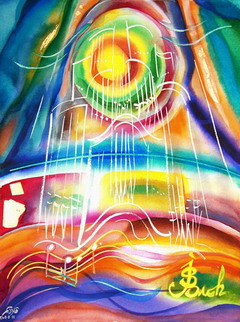

BACH (2)

|

May 17, 2005. This painting was made at the request of a friend who suggested using Bach’s music. The white vertical lines are inspired by seeing a photo of the beautiful organ recently reconstructed at Thomaskirche, Leipzig, Germany [26]on the lines of an organ that Bach himself had helped design. The notes in the painting were copied from a manuscript in Bach’s hand for Cantata BWV 82 "Ich habe genug" .[27] In the bottom right corner is my rendition of Bach’s beautiful signature written on his Bible .[28] The music pieces I heard while making this painting were: J. S. Bach's Harpsichord Concertos BWV 1052, 1054, 1055, 1056 and 1065 , the Golderberg Variations and the Inventions. I also made a larger version of the same painting, signed on June 1 2005, while listening to Bach’s Masses BWV 235 and BWV 236. Once again Bach’s music, with its incredible mixture of solidity and richness of musical form, and emotional flow, inspired me to make a strong and assured painting. |

BEETHOVEN (4)

|

October 2005. I started this painting without intending it to be part of this series. I had woken up one morning having dreamt of making a painting featuring a large balloon-like shape dominating the bottom of the painting and at its center the cluster of transparent shapes making up a star. Doubtless the followers of Freud can discover amazing and unexpected things from this about my psyche. Anyway I actually painted these shapes remembered from the dream, and for four weeks after that I just looked at the painting, occasionally adding some smooth indistinct shapes. It was all very placid. Until the day I listened to the Kreutzer’s Sonata (No. 9, for piano and violin played by Kremer and Argerich), downloaded from the Internet. I put on the computer’s speakers at full volume and listened and painted. It was incredibly beautiful and I started painting furiously, finishing the painting in the 37 minutes and 43 seconds it took the music to play. I had fallen in love with this perfect piece of music – precise, dynamic highly inventive and emotional all at once- in my university days in Lebanon. My friend Tony Shebaya repeatedly played an LP record of the Kreutzer in the dormitory, in order to remember it for a music-appreciation exam. He passed with flying colors, and I am ever thankful because he introduced me to this brilliant music. |

PERGOLESI

|

December, 2005 Pergolesi's music is always gentle and full of light, even in his most passionate passages. The lyrical transparent music employs simple but effective musical devices- often a clear ethereal melodic line accompanied by a harmonious background. The wonder of his artistry is that in his greatest and last piece, the Stabat Mater, he could evince emotional depths without overloading the music with noisy or out of the ordinary musical contrivances. The square pattern to the top right was painted while listening to a vivacious excerpt from the Concerto for Violin and Strings in B flat. The music held and guided my hand to draw the curvaceous lines dominating this area and the rest of the painting. I also listened to his Salve Regina, the Magnificat and the delightful comic opera La Serva Padrona. The painting came easily to me because at the time when I first fell in love with Pergolesi’s music in my early twenties (I only knew his Concerto in G then), my abstract art consisted almost exclusively of lines and simple color-loaded brush-strokes, a style I used in this painting. And which suited Pergolesi’s pure graceful melodies. Pergolesi never had the chance to fully develop his marvelous talent since he died of influenza at the age of 26 just after completing the Stabat Mater. This painting is a tribute to his brilliant short life and in some ways, to my own “lost” youth. Lost only to be thankfully revived while listening to this luminous uplifting music. |

BACH (3)

|

March, 2006. After decades, and thanks to email, I resumed contact with Ibrahim Souss. He responded enthusiastically to my paintings to music, and suggested I make one to the Aria and Thirty Variations (BWV 988), known as the Goldberg Variations, Bach’s keyboard masterpiece. This famous work of 1741 was commissioned by Count Keyserling for his own private listening pleasure, during his bouts of insomnia. He had employed Johann Goldberg a brilliant harpsichordist, and Bach himself gave the young musician lessons. The exceptionally difficult piece is made up of an Aria, a hauntingly beautiful saraband or dance, followed by thirty variations. Every third variation is a canon, (a musical form in which the melody is repeated), and at the end the Aria itself is repeated. Instead of making the variations using the main melody of the Aria, Bach used the bass line. After much thought, I decided to divide the painting simply into 32 regular rectangles. The calligraphic golden lines in the Arias (upper left and lower right) are my response to the melody, and I overlay similar lines slithering all over the painting, simulating the common thread joining all the individual variations. I then painted each variation in turn listening to four different versions of the music, using yellows only in the Canons. The penultimate square just before the final Aria is my illustration of Bach’s musical joke. He ended this exalted and masterly piece of music with his rendition of two ‘pop’ songs of his day- something about cabbages and turnips! I repeatedly listened to three piano performances of the Variations, the two bravura recordings by Glenn Gould (1955 and 1982), and to the equally beautiful but more classical interpretation by Angela Hewitt, and to Masaaki Suzuki’s performance on the harpsichord. |

SHOSTAKOVITCH

|

August 2006. As a young man I knew just a few of Shostakovich’s visceral works. Kyoko and I adopted his name as an expression of amazement - "Shostakovich!!” I remembered his two characteristic moods: violent excitement and hyper-sensitivity. With the news of the awful war in Lebanon dominating my thoughts, I started this painting listening to the music of this Soviet musician who started his 7th symphony in Leningrad while Hitler's army surrounded the city and bombed it to rubble. A musical Guernica. Once again I fell in love with the best of his music, the First Cello Concerto, the quartets, some of the symphonies. I was very impressed with the opera Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk. Here was the perfect vehicle to demonstrate Shostakovich’s dazzling capacity to express certain moods. The personal tragedy of the peasant lovers is contrasted with the turbulence of the public life of that era. The opera ends in a harrowing murder-suicide in a Siberian prison camp. It was written at a time of unprecedented interference by the State in the artistic creations of its citizens. Stalin attended the first performance of this opera and disapproved. It was banned for decades afterwards. The composer changed his musical style and avoided the purges that eliminated many of his fellow musicians. Not all of his music is inspiring. At moments I felt myself saying "oh no, not again!" as I listened and painted. A friend said he can take Shostakovich in small doses. He was described as the greatest of eclectics- one hears musical snatches from Tchaikovsky, Katchadurian, Chopin Beethoven, Bloch, Rossini and others. The crescendos are of Mahler's world. I also heard bits of Prokofief's Peter and the Wolf casually inserted in his music. I fancied that this musical story for children contains the three themes that dominated Shostakovich’s entire oeuvre, which also became the three themes in my painting: 1- The trills and gossamer strains of prayer-like passages (the bird in Peter and the Wolf - thin trailing lines in the painting). 2- Noisy primeval outbursts of triumph and anguish (the deadly attack on the wolf - the center of the painting), and 3- Brash confident enthusiasm and rejoicing (the noisy joyful ending march with Peter and the hunters- the dark horizontal shape in the lower half of the painting). Like a masterful Zeidan in soccer, Shostakovich would receive these musical passes from his musical team-mates and run along with them, often scoring a goal. Shostakovich himself was a devoted soccer fan and his ballet The Golden Age features a soccer match. He survived both Stalin and Hitler, and perhaps that is why his music is still so moving and popular- it is about human steadfastness and survival in the face of adversity. As a personal note I met three prominent figures from the Stalinist era. Freda Utley the English author (whose Russian husband disappeared in Stalin’s purges) became a friend and encouraged me as a budding artist. Once I chatted with (and sketched) Solzhenitsyn, himself the famous survivor of the same Gulag featured in the Lady Macbeth opera. And as a student in Beirut I attended a poetry recital by Yevtuchenko, on whose poem Babi Yar Shostakovich based his 13th Symphony. It commemorates the massacre of Jews and gypsies by the Nazis. As I painted to this moving symphonic oratorio I could not help thinking of my own 1982 painting Homage to the Victims of the Sabra-Shatilla Massacres, which occurred when the Palestinian camps in Beirut were surrounded by the Israeli army. Long after the costly political experiments of the 20th century become just a memory, the world will thrill at the beauty of Shostakovich’s First Violin Concerto, as I heard it performed on a borrowed CD by Midori. |

SCHOENBERG

|

November 2006. I started out with the wrong impression of Schoenberg: Only knowing about his innovation of 12-tone music, I assumed that his work was analytical and austere, so I carefully chose twelve colors to make the painting with, and started the painting drawing twelve shapes morphing in twelve shades of green. To my surprise I found his music mercurial, lyrical, tense, thoughtful and explosive in turns. After that realization I used a full-color scheme - his 12-tone musical scale was just a conceptual tool, and not an end in itself. In many passages I could not help thinking that musicians writing for film had lifted whole passages of his music for their exciting scenes- rolling vistas full of feelings of hope and happiness, or suspense scenes in dark corners. Specifically piece # 4 in his Five Orchestral Pieces Op. 16 may well have been the direct inspiration for the writer of the hunting scene music of Planet of the Apes. I later discovered that in fact Schoenberg had written Accompaniment to a Cinematographic Scene - Threatening danger - fear - disaster Op. 34 (1929–1930) specifically to be played at silent-film theatres! [36]This in no way lessens the greatness of his music. Schoenberg, like Schubert before him, was blessed with an ability to feel deeply, and to transcribe his feelings precisely in original musical terms almost as they may have occurred in real time. His mind was always inextricable in touch with his heart. That is why his music, for all its abstract modernity, is so accessible and unburdened with aesthetic programs or philosophical baggage. A good example of this is Psalm 130 for a mixed chorus of six voices Op. 50 B (1950). In this Biblical invocation for Yahweh's succor and mercy the voices sing the words. "From the depths I cry to you O Lord" with great feelings. To Schoenberg, who was a devout Jew who had lost family and friends at the hands of the Nazis, this Psalm may have been sung by the victims of the Holocaust. Ironically when I hear this music, it is also the sufferings of my fellow Palestinians and Lebanese, very possibly at the hands of some of the descendants of those same victims, that first come to mind. From the excellent website devoted to Schoenberg[37]I learnt that the same brilliant mind that helped him translate his feelings into clear and original musical language, also led him into other activities. He was an excellent artist who discussed art and music with Kandinsky and exhibited with the Blue Reiter artists. He was invited (but refused) to head the music department of the Weimar Bauhaus School. He was an inventor holding a patent for a sophisticated musical typewriter (1909) decades before such a typewriter became practical. Among his other designs was an electric typewriter, a four-player variation of chess, and designs for a charming set of playing cards. These can be purchased today at the Schoenberg Center shop, or ordered online for 33 euros (add 8 euros for shipping). Lastly, he was a significant figure in the history of visual music: he gave extensive detailed instructions for his opera Aaron and Moses to be performed as a monumental synthesis of the arts, following the ideas of Wagner and Scriabin in that regard. |

BACH (4)

|

December, 2006. In a bizarre incident that could only occur in a wasteful consumer society like Japan, I recently found many almost-brand-new CDs thrown in a trash can at a small park, so of course I picked up this treasure trove. Most of them had organ music, and one box set of 16 CDs had the entire surviving pipe organ oeuvre of J. S. Bach beautifully played by the late Werner Jacob. This painting is the result of 16 day’s work listening to the complete set; one CD a day, while painting. Mozart called the pipe organ ‘the King of instruments’. If musical instruments were likened to landscapes the pipe organ would be both Everest and the Grand Canyon, and many other vistas in between. In warfare it would be a tank brigade. As a building it would be - what else- a cathedral! In fact this uplifting music, often written by Bach for use in church, influenced my painting (albeit unconsciously) to evolve into a pattern of pointed arches, vertical ‘columns’ and even the flying buttress shapes at the top corners. The strong pointed arch that emerged in the center of the painting reminded me of the marvelous arched halls, traditionally made entirely of reeds by the Marsh Arabs in Southern Iraq. (Unfortunately their way of life has been almost wiped out by the wars and oppression that have blighted the region in recent years.) Bach was a pipe organ virtuoso best known in his lifetime as a performer not as a composer [38].He would work the multiple keyboards and foot pedals and the stops (the knobs that controlled the timbre of the sound by channeling the flow of air through chosen sets of pipes), all seemingly without effort. This powerful instrument gave a range of sounds that depended on the length and shape and the pipes and the materials out of which they were made of, be it wood or a lead-tin alloy. The resulting music could be anything from a mighty vibration that is felt through the feet of the listeners, a plaintive whine, a high-pitched whistle, or a glorious blast of sound from hundreds of pipes together that is unlike that produced by any other instrument. Almost no strength is needed to make all this music: I could testify from personal experience at a church organ how drunk a person can become with the mighty sounds being produced just by exerting a little pressure! In Bach’s hands (and feet), the music is compelling as well as beautiful and uplifting. I listened and painted to the well-known blockbusters like the Toccata and Fuge in D Minor BWV 565, and the equally great Toccata and Fuge in F major, BWV 540. The Fugue in C minor, BWV 537, is made of thick `bundles` of interwoven chords and tones flowing together without pause, in a grand richly-patterned assemblage of a deep brooding drone, supported by other smooth tones, and topped by the brittle soprano flute notes that I always felt were a bright yellow. Fortunately for my nerves, Bach also wrote many quiet idyllic pieces with muted tones, like the Fantasia in C minor BWV 562 and the sunny unfinished Fuge that followed it. Or exquisite miniature gems like Orgel-Buchlein Nos. 30-32, Chorale: Erstanden ist der heil'ge Christ, BWV.628 where the sound seemed to me like a small piece of multicolored weaving, or the very agile joyous music of Clavier-Übung III Chorale: Jesus Christus, unser Heiland (BWV 688). |

RIMSKY-KORSAKOV

|

February 2007. Sheherazade is one of my favorite pieces of music. I know it cannot bear comparison to the really great ones- Bach's Brandenbourgs, Mozart's piano concertos or Beethoven's Kreutzer Sonata, but the Sheherazade is perfect in its own way. It seems to have everything: Color, passion, excitement, delicacy, precision, economy of musical writing, and a satisfying range of emotional expressions ranging from the overwhelming to the most lyrical, all seamlessly progressing from start to finish. Of course the music purports to tell the the story of Sheherazade the enchanting storyteller of the Arabian Nights. It is purely escapist music, so much fun to listen to that one of its phrases was sung by me and my young daughters when running outdoors "tat-ta-raaaaaaaaaaa- tararara tat-ta-taaaaaaaaaaa". The late Edward Said, author of Orientalism, whom I had the privilage of meeting in Tokyo, would point out that the whole European obsession with oriental themes was part of an imperialistic mindset. Even so, the Arabian Nights is part of our culture- the simple people of the Middle East, experiencing the horrors of continuing wars and invasions, needed to escape into a world of fantasy and romance. This was true even at the height of Nasser's revolution in Egypt when one of the best children's magazines in Arabic was first issued. It was called Sindibad and its chief illustrator Bikar (which means "compass") made such beautiful drawings for stories from the Arabian Nights. He used such clean sinuous lines that I copied. In this painting, entirely made during one listening to the music, these lines are transformed into broad brushstrokes full of various colors. Which brings us back to Rimsky-Korsakov, who was said to be synethsetic "seeing" musical notes in color! |

[24] www.mozart-mp3.com/ a radio station from Milano, Italy. [25] Vladimir Tamari, A Beautiful Universe, work in progress based on research starting from 1993 [26] The organ Bach used, see the white enamelled organ from: http://relativity.phys.lsu.edu/postdocs/matt/pipe_organs.html [29] Feisst, Sabine M. “Arnold Schoenberg and the Cinematic Art”. Musical Quarterly, Vol. 83, No. 1 (Spring, 1999), pp. 93-113

|