PAINTING THE MUSIC

Vladimir Tamari

TAKEMITSU

|

June 2008. Without knowing it I had listened to the music of this unique Japanese composer shortly after Kyoko came to Beirut and we were married there in 1967. We attended two Japanese films, Seppuku and Suna no onna (Woman of the Dunes) whose music was written by Taro Takemitsu (he also wrote the music for Kurosawa’s Ran and The Rising Sun). Soon after that we moved to Japan, and over the years I have listened to a great variety of Japanese music ranging from the expressive sound of the shakahachi bamboo flute, the shrill and haunting Gagaku court music, thrilling folk songs and taiko drum performances, the highly-strung singing and instrumental music accompanying Noh theatre, and to others. Takimutsu knew these sounds deep in his soul and he used them all in an eclectic music he melded smoothly with other influences from modern Western and Asian music. He must have loved Debussy’s Pelléas and Mélisande because its haunting music inspires many passages of his compositions. Thus Japonism, the craze for all things Japanese that helped inspire Impressionism in art and music in Europe, now returned to Japan. Another source of inspiration was the experimental music of John Cage, whom Takemistu befriended. The miracle of Takemitsu's music is that he has converted these disparate elements into a coherent whole - a Japanese musical language that varies between powerful controlled outbursts and the gentlest passages that seem to have been played by a somnambulist. For the most part Takemitsu's haunting music is almost self-effacing - one hears it, lives it and is then enveloped by silence. It is very Zen, very modern and very enjoyable. I felt thoroughly at ease with this music of my adopted country and the painting came out well. There are several virtual connections between my life in Japan and Takemitsu's. When Stravinsky conducted his works in Tokyo, Kyoko was in the audience; it was then that the young Takemitsu met and was praised by the master. Many years ago I did illustrations for a Japanese children's book of Ali Baba and the 40 Thieves [42]. At the publishers I met Takemitsu's friend the poet, Shuntaro Tanigawa who had edited the book’s text using a strange pen-name. It was only now that I listened to the music that Takemitsu had made for Tanigawa's evocative and gentle poems. And then there was Kohei Sugiura who commissioned me to draw the decorative Arabic titles for the book he was designing on Palestinian Costumes[43]. Around 1962 Sugiura had collaborated with Takemistu to make interlocking colored circular prints that were used as a 'score' and interpreted chaotically by the string players in Corona and Corona II [44]. This significant 'visual music' experiment was inspired by John Cage's interest in the relation of art and music.

|

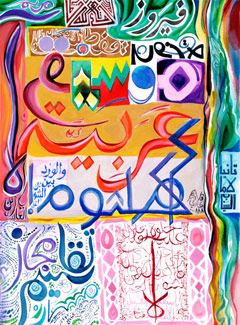

ARABIC MUSIC

|

July 2008. For months I had been hard at work trying to complete my design of an Arabic font I called AlQuds (Arabic Jerusalem). It seemed appropriate to dedicate a painting to Arabic music [45], and paint it entirely using the names of musicians and excerpts of the lyrics written in various Arabic calligraphic styles. When I grew up in Palestine the music I heard on the radio or record player at home was mostly Western- anything from Madame Butterfly to American pop songs and musicals. Once my aunt's family was visiting from Syria and their young servant girl called Sultaneh sang some folk songs that linger in my memory for the purity and sureness of her voice. I also learned hauntingly beautiful Palestinian folk songs such as Hawwel Ya Ghannam Hawwel and heard Ramzi Rihan’s piano variations on that tune. In public, in the taxis, at the barbershop, the falafel seller's kiosk, and everywhere in the shops and suqs of Ramallah and the Old city of Jerusalem blared radios with loud rhythmic Arabic songs. It was inescapable, and I little appreciated it, except for the beautiful songs of the Lebanese singer Fairouz - I wrote her name on the top right edge of the painting as I listened to her sing Holy Week church songs in Arabic. Listening to this great variety of music, including popular songs, I singled out three 'moods' characterizing Arabic music: 1- Tarab (musical enjoyment): joyful, exciting extrovert and rhythmical 2- The Ah moment- when the music suddenly lifts to a prayerful soulful purity and calm with long plaintive tones, 3- The Ya Ein Ya Leil (O Eye O Night) moment with unabashedly sensuous even erotic passages and 4-Virtuoso variations in key and rhythm when the music changes to various well-established maqams (modes) that can be as sophisticated as a Bach could make them, and that date back to centuries before his time. |

CACIOPPO

|

September 2008. Curt Cacioppo [47]is a contemporary American composer whose music classes my daughter Mariam had attended at college some years back. He had kindly sent us a copy of his CD entitled ancestral passage of his string quartets that have titles and themes related to the Native American Navajo tribe: Coyoteway, The Ancestors (which was inspired by a painting of the same name by Charles Stegeman), A Distant Voice Calling and Snake Dance. Cacioppo's interest in and research into Navajo ceremonial music is deep and sincere, but except for a few overt quotations, this influence in his music is indirect. His pieces are very much in the European tradition of string quartet writing ranging roughly from the soulful late Beethoven, to the free-wheeling angst-ridden, exciting or petulant outbursts of the moderns such as Bartok Schoenberg or Stravinsky. Caccioppo skillfully wove his own music to produce vigorous, very lucid and evocative music. In my painting I included some patterns drawn from Navajo crafts and ceremonial objects dominated by the central figure of the Yeii Spirit, a mediator between humans and their Creator, and the circular 'dream catcher', based on the exquisite netting crafted within a wooden frame. Both the Palestinians and Native Americans have had their lands, much like the proverbial rug, more or less pulled from under their feet. It is a testament to both these people's inner strength, that they tenaciously cling to their identity and culture, even as they try to survive in a very different world often hostile to their original ways of life. |

MOZART (4)

|

October 2008. When I first read about Mozart for this essay many years ago I was struck by the words that Mozart's piano concertos are a 'world of their own'. Of course I have heard several of them over the years, but I wanted to hear them all! That is exactly what I did when I made this painting. On the first day I heard piano concerto No. 27 (his last) and worked within the left third of the painting while I listened to the first movement, The central panel was reserved for painting to the second movement and the third was to the right. I did not actually paint at first, only applied a masking solution (as wax is added in batik) which prevents further painting on the area it covers, and is only removed to reveal the colors once the painting is complete. This is a standard watercolor technique I had used before for example in the Caccioppo painting where the masking leaves the white lines. Next day it was the concerto No. 26 and I applied colors over the masked lines, following the system of representing the concerto movements in separate partitions. I was in seventh heaven - the music was incredible and the painting reflected some of its gripping drama. On the third day I added masking to the painted parts while listening to the 25th concerto, and continued alternating masking and painting as I counted down the concertos. But by the time I reached the 16th concerto a couple of weeks later, the painting was crowded with colors and masking solution, but I decided to go on nonetheless, and perhaps this was a mistake. By the time I reached the first independent piano concerto by the young Mozart (No. 5 - the earlier Nos. 1 to 4 are rearrangements of the music of others and I did not listen to them) the painting was a mass of overcrowded colors and shapes. Listening to the concertos in the reverse order in which they were composed was instructive. The earliest are brilliant and passionate -No. 5 was written when Mozart was 17, just a teenager. But they sound like honky-tonk music if compared to the last seven or so concertos where the piano part (perhaps infused with Mozart's 'ego'?) is deeply and subtly integrated with the surrounding music of the orchestra. Towards the end he had developed this art form to a degree where, in the middle of a sunny extroverted run he would modulate the tune and the rhythm to open his soul in the simplest and most revealing way. No wonder that Einstein, (who loved to play Mozart's music on his violin), said that his music was "so pure that it seemed to have been ever-present in the universe, waiting to be discovered by the master." And what of the painting? Perhaps it reflects some of the energy, fluidity and precision of the music to some degree. But compared to what the piano concertos 'deserve' in a painting, it is just a glorified psychedelic dyed T-shirt- a monument to the vanity of a painter who tried to paint listening to the complete set of Mozart's piano concertos! |

MESSIAEN

|

December 2008. It happened that I started this painting four days before the centennial of this French composer's birth on Dec.10 1908, and again it was music that was all new to me. I was pleasantly surprised by the combination of serene and sincere religious music stemming from Messiaen's Catholic piety, together with a strong sense of modernity and exuberant experimentation with percussion effects. Messiaen had a mild form of synesthesia and theorized that color was an essential quality of music. He described one passage that was "blue-violet rocks, speckled with little grey cubes, cobalt blue, deep Prussian blue, highlighted by a bit of violet-purple, gold, red, ruby, and stars of mauve, black and white. Blue-violet is dominant." [48] He also considered himself as much an ornithologist as a musician and studied birdsong around the world, incorporating it into most of his compositions. A case in point is his marvellous Des canyons aux étoiles… (From the Canyons to the Stars...) a piece privately commissioned to celebrate the bicentennial of the US Declaration of Independence. Several of this composition's 12 movements have the names of various birds while the others had poetic names related to geographical features in national parks in the state of Utah, which he visited in 1972. This positive and thrilling music alternates between loud sweeping chunks of sound and staccato passages depicting the movements or calls of birds. It is music made by or accented by all sorts of percussion instruments, including a wind machine and the geophone that Messiaen himself invented (a large metal pail full of steel balls that produces a swirling-rattling sound). This most apolitical of compositions ends with a movement named after an an actual Earthly scenic paradise and a spiritual one: Zion Park and the celestial city. It was bitterly ironic for me that I was enjoying this inspiring music even while the news of the bloody US-approved Israeli attacks on the people of Gaza were fresh in my mind. |

STRAUSS

|

January 2009. Richard Strauss (not his waltzing namesakes) is not squeamish about expressing strong emotions. I wanted to listen and paint to his many compositions throughout January. Instead, the bloody Israeli invasion of Gaza was foremost in my mind. It was also the bright New Year 2009. On the 7th I started listening to Strauss' Thus Spake Zarathustra, the short symphonic poem with the dramatic opening theme used at the start of Stanley Kubrick's famous movie 2001: A Space Odessy. I was so keyed up about Gaza and started the painting with a strong vertical green shape, perhaps thinking of an abstracted symbol for the Palestinian stand. The Israeli onslaught was depicted by the blue shape driving into the green. As it happened the result was aquamarine, but I draw no political conclusions from that! As the dramatic music progressed from Dawn to the other movements (corresponding to the philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche's book from which the piece's title was taken), I was painting at full speed and concentration, adding the gold at the center to cover the dark area there. The painting was completed in real time with the music - about half an hour, and was not retouched later. |

BARTÓK

|

March 2009. Bartok's music is passionate, tense, terse, inventive and pungent; it can be richly evocative and calm or cacophonous in a brilliant captivating sort of way. One savors it as distilled Stravinsky on the rocks flavoured with Schubertian melodiousness. I made this painting in seven sessions, painting to: 1- The Concerto for Orchestra and the Dance Suite (in the large central white area); 2- The Miraculous Mandarin ballet and Divertimento (top right corner); 3- Sonata for Two Pianos and Percussion (middle of right edge); 4-Second Violin Concerto (top left corner); 5- String Quartet No. 1 (lower right corner); 6-String Quartet No. 2 (red striations in the middle of the left edge) and String Quartet No. 4 (the beige and dark browns under the red); 7- Bartok's remaining String Quartets: No. 3 , No. 5 and No. 6 (Bottom left corner all in vertical stripes: blues for No. 3, orange with gold for No.6, and between them No. 5's five movements left to right in greens, brown lines, blues. pinks. and violets). |

|

[42] Ali Baba and the Fort Thieves. 1976 Labo Teaching Information Center. Download a pdf of the book 43]Costumes Colored By The Sun, Edited by Wada Kawar. Bunka Shuppan-Kyoku. Tokyo 1982. [44] Burt, Peter, The Music of Toru Takemitsu http://books.google.com/books?id=MlHI_Nv5HC4C&hl=en [46]http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hamza_El_Din listen to Hamza's music from External links. See his painting on his official website. [48]Traité de rythme, de couleur, et d'ornithologie (1949–1992) ("Treatise on rhythm, colour and ornithology"), Paris: Leduc, 1994–2002

|