PAINTING THE MUSIC

Vladimir Tamari

BACH (5)

|

June 2009. On my Facebook profile I declared to the world that Bach's celebrated Brandenburg Concertos were my favorite pieces of music. Here they are visualized in six panels one for each concerto, strarting top left and going left to right, the 4th being on the bottom left. Again I used the resist method to draw white lines while listening to each concerto once. Then I listened to the music again to apply the colored washes. Using Bach's own words in dedicating these pieces, I apologize for the meagre technical means I used to make this painting: " begging Your Highness most humbly not to judge their imperfection with the rigor of that discriminating and sensitive taste..." Ever since I heard them in the early sixties and made my short film of colors pulsating to a passage of one of these concertos, this music has been a sure tonic for me to uplift, excite, console, and inspire. My favourite of the suite is the sixth and last (bottom right). In the first movement I drew 'wild' lines all over the square and thought of Jackson Pollock. I had not appreciated the importance of his 'action painting' in relation to visual music until recently, when I saw the epynomous movie about him. Here was real-time color-shape-movement. With this Bach I started drawing a pattern of white lines reminiscent of Lissajous figures - 'baroque' harmonic criss-crossing mathematical curves such as seen on an oscillescope. For the 2nd and 3d movements I used a finer nib to embellish what I had drawn so spontaneously. An odd thought struck me that this polyphonic, vibrant, lucid, relentlessly inventive and deeply moving music could well be a symbolic distillation of all of human emotions, scientific ideas and artistic constructs... experienced simeltaneously! |

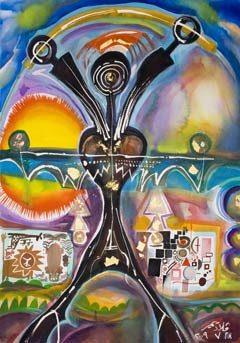

AFRICAN MUSIC

|

July 2009 - Perhaps the idea to make a painting listening to African music came to me when I read an article about the recent discovery of the earliest artwork and musical instrument. The 'Venus' figurine was carved of mammoth ivory, and a flute made of bone lying nearby were both discovered in Germany and date back some 35,000 years. Using DNA evidence, scientists estimate that this was soon after humans emerged from Africa, where we had had evolved even earlier, from a single woman, the so-called Mitochondrial Eve. Africa is about race after all..the entire human race, and some of its music expresses our spirit in its purest form. I started listening to a CD African Tribal Music and Dances - a woman was singing a piercingly high-pitched hymn of praise Kerena. This immediately set the mood for the painting conjuring all sorts of 'Africa' seen in photographs, museum artifacts, issues of National Geographic, typical African wooden sculpture and Picasso's painting influenced by African masks. As I listened to other chants, dances, percussion pieces and songs I started drawing an abstracted female figure of triumph and joy - black Venus or Eve dominating the painting. The music I listened to was eclectic (but far from comprehensive) ranging from traditional drums, the songs of Miriam Makeba which symbolized African Independence movements, Ethiopian church music, and even reggae, heavily influenced as it is by its African roots, and the mellow cadence of Ahmadu and Miriam, the blind singers from Mali. But it was the remembered music I had heard live that I tried to conjure as I painted. The gentle drumming and songs of my late Nubian friend Hamza El Din, can now be heard online [46], and the unforgettable memory of a 1986 performance in Tokyo by drummers and dancers from Burundi. I even remembered listening as a boy in Ramallah to a famous African-American singing a deeply moving song- perhaps Old Man River from Showboat. Was it Paul Robson himself? Early American Jazz of course has strong African roots, but I found that I had finished the painting before I listened to any. I tried to learn about African music written in a classical idiom, and learned about Joseph de Bologne, the Chevalier de Saint-Georges - the 'Black Mozart' -a brilliant Afro-French musician and France's best fencer during the time of the French Revolution. Alas his music, accomplished as it was, was even tamer than Hayden's. One hopes that a great music encompassing the unique spirit of Africa expressed in a classical orchestral tradition has been or will be composed. |

POULENC

|

| September 2009 - I started this picture by painting the large rectangular area in the center while listening to a recording of Mariam sing Poulenc's song Violon[49]. She had encouraged me to listen to this modern French composer's music and I was very happy to do so. I found his music always enjoyable, focused and neat, even at its most fluid or emphatic. He has been called 'the poet's musician' because of his friendship with many poets and his putting their words to music. It was a pity my French was only good enough to get only the gist of the words of many of his pieces. Even the titles, like Figure Humaine (meaning The Face of Mankind, from the poem by Paul Éluard vilifying the Nazi occupation - the densely painted area top center of the painting) are beautiful and meaningful. I specially liked his Gloria (the convex shape based on the entire lower half of the painting) and Stabat Mater (inverted L-shaped area top right corner). The fervor of his religious pieces is in contrast to the jaunty lighthearted song cycles - yet one feels Poulenc is always being entirely honest with himself, and hence in his exuberant, melodious, and - to use a sadly neglected old word - quickening (i.e. life-giving) music. |

PURCELL

|

|

November 2009. Although it is based, on Shakespeare's Midsummer Night's Dream, I started painting this picture, listening to Purcell's The Faerie Queen the delightful opera based on that play, in the autumn of the year, and indeed of my life. Purcell's music won me over completely. Before the Romantics, before even Bach and Handel, here was brilliant exciting confident vocal music for operas, prayers (even tavern songs) all sung in the English of Shakespeare and the King James Bible. I started the painting by sketching the Queen in bold outline and spent weeks refining the image, listening to other Purcell music, including Dido and Aeneas and various vocal pieces composed for the Church. In the 'Chinese Dance' of The Fairy Queen I found traces of La Folia, an evocative saudade (sad-sweet, the only Portugese word I know) tune from Portugal that weaves a thread in Western music. I had loved La Folia ever since hearing the Corelli and Vivaldi variations on it. A bit of googling confirmed that the tune crops up in many of Purcell's compositions. Another discovery was that Handel almost certainly was inspired by Purcell when writing some of his great oratrios for example the Messiah. All of this reawakened in me an old Anglophilia that had survived the knowledge of the modern British role in the disasters that overwhelmed Palestine. There is something in me that finds comfort in self-assured and idiocentric island cultures such as those of the English or Japanese, and hearing English sung in such accomplished and regal music reminded me of the year I spent as an art student in the same London as Purcell's. Coming to think of it the Queen I drew is basically a caricature: one of my earliest ambitions as an artist (unrealized) was to publish a cartoon in the British humorous magazine Punch. The magazine has folded, but thankfully Purcell's glorious music will survive the centuries. |

BRUCKNER

|

December 2009. A few years ago I read about the monumentl work of Jack Ox to create a series of paintings in oils that were a visual representation of Bruckner's 8th Symphony. She also spearhead ed an ambitious project, using a supercomputer and virtual reality technology, to transpose this symphony into animated 3D graphics - note by note. She calls the setup a 21st Century Color Organ [50]. This inspired me to choose this particular work by the Austrian composer to paint to, but I approached the work in a very different, less systematic way, hoping to achieve a spontaneous painting reflecting the spirit of the music as a whole. In any case that is the best one can do in a watercolor. I put on the 2 CDs of Herbert Von Karajan conducting the Wiener Philharmonic in 1988, the year before he died, and painted the picture in one session with no subsequent revisions. I listened to the music once, dedicating an area of the painting to each of the four movements. [The first movement in purples and pink in the left and top edges; the 2nd movement in yellow-greens and beige, right and bottom edges; the 3d movement in the middle in grays and blues, surrounding the 4th movement in the center, mainly in reds]. The music consisted of a fascinating mixture of the powerful statements of Beethoven, and the fluidity of Wagner, but it also had had another unique and gentler element hard to define. A strict Catholic, perhaps Bruckner was expressing religious feelings as well as the more usual Romantic effusions? The critic Ted Libbey writes that "Karajan's careful pacing gives the Eighth time to unfurl, allowing the mystery and tenderness of Bruckner's vision to radiate from some place deep within the paroxysmal intensity of the symphony's argument." Exactly!

I used a large calligraphy brush (once used by my mother-in-law Hoshiko in her beautiful Japanese calligraphy works) and the painting came out very succinct and Japanese. It harks back to Sesshu the Zen priest whose emaki (monochrome landscape paintings made with black sumi ink on paper scrolls) had inspired me so long ago. Sesshu in color! These patches of color surrounded by white also owe a debt to the lovely watercolors Cezanne made of Mont Saint-Victoire. I had two other recordings of the Symphony and was tempted to continue painting. Luckily my wife Kyoko confirmed my doubts, took a look at the painting and said "don't work on it any more". |

CORELLI

|

January 2010. Why did some 150 different composers since the mid-seventeenth century choose to write their own version of La Folia - said to be the oldest tune in Western music?

How far back does the melody go? Folia (foolishness) was an exuberant Iberian dance, but it may well have had a different and earlier Arab-Andalusian origin. I muse that somehow the music was associated with recitations of A Thousand And One Nights "Alf Laila wa Laila"...Alflaila...La Folia In fact if one splits some of the notes into quarter notes the melody would be indistinguishable from some heartfelt Arabic love song! |

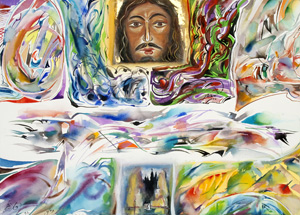

RACHMANINOV

|

February 2010 . As with Liszt I had avoided painting to Rachmaninov's music as much as I could. His piano concertos lingered in my mind with their visceral showy intensity. But upon listening to his music I now find that the intensity comes from the technical virtuosity of the dense music, driven by a consistent expressive logic. The element that saves the music from being mere wayward Chopin-gone-wild exhibitionism is its rock-solid sincerity. It is hard to define this quality, but one can feel a unifying cultural tradition, a stable personality' behind the seemingly haphazard and rapid changes of mood that characterize most of his compositions. In the beginning of the this essay I mentioned how Rachmaninov composed The Isle of the Dead after seeing Böcklin's painting of the same name. There are various versions of this painting to be seen online, [52] and I listened to the music watching the original on my monitor as I tried to make my own version of the painting at the center bottom of my watercolor. I soon gave up all pretence of reproducing anything but a hint of this magnificent and haunting painting. I could respond more positively to Rachmaninov's music for the Liturgy of St. John Chrisostom (the icon of Christ at the top), since for some two decades in Japan I had worshiped regularly at Nicolaido cathedral. where the choir sang the hymns in the rich and moving style of late Russian church music. This was a sort of prettied-up Byzantine music, yet full of the intensity of the faith that prevailed the Czarist Russia of Rachmaninov's time. I also painted several traditional icons over the years. The rest of the painting is devoted to his more traditional music - two of his Piano Concertos flanking the icon, and at the top edges two of his Symphonies. Amazingly much of Rachmaninov's music, including pieces he wrote around 1919, was recorded with himself at the piano, and is available today. The primitive recording methods dampened the dynamic range of the music, so that it sounds mellow and distant, but it is so brilliant and beautiful. |

INDIAN MUSIC

|

May 2010. Over the years I have developed an appreciation of various aspects of Indian culture - most importantly for me as an artist is the use of strong colors. There is even a joyous Indian festival Holi, devoted to color! Once my daughter traveled to Madras to attend the wedding of a friend, and in the photos there was an unabashed yet harmonious display of color particularly in the fine silk saris. Having just finished E. M. Forster's evocative novel A Passage to India (in which one English character is baffled by Indian music) I decided to devote a painting to the subcontinent's music. Here is a continuous musical tradition going back thousands of years. One feels this maturity in the matter-of-fact way the devotional raag singers and players dish out a splendid feast of the most intricate, sophisticated and moving sounds. There is none of the self-consciousness of Western classical musicians in their black suits and bow ties performing a late Beethoven quartet, even though the rarefied beauty and power of the music is comparable. One thing that struck me about Hindustani music is that various modes or styles are played during (or at least named after) eight prahars or set periods of the day for example from 6 to 9 pm. One prahar is for (or of) the monsoon season (which I painted in red at the bottom right edge). I really doubt Vivaldi knew this form when he wrote his Four Seasons! The other prahars are painted to in two rows (1-5 and 6-8 below it) starting with the blue rectangle in the center of the painting. Quite different in spirit is the intense emotionalism of Tamil devotional and popular songs (entire left edge of the painting). |

MONTEVERDI

|

August 2010. Most of the enchanting music I heard while making this painting was vocal. Monteverdi did not invent the opera form, but a few decades after it was, he wrote its first masterpieces. In his large musical output in styles spanning the late Renaissance and the early Baroque, he had ample preparation for this accomplishment. He wrote scores of madrigals, sacred or secular music for up to eight voices with minimal instrumental accompaniment. Words and harmony where of supreme importance to Monteverdi and he excelled at expressing all sorts of emotions with them, even though musical tradition demanded a measured courtly delivery. It is astonishing to learn that some 17th century critics called this polished delicate music - at least to our modern ears - 'barbaric'. The miseries of a Tokyo summer were made tolerable for me listening to some of Monteverdi's 'cool' madrigals and painting the abstract portions of this painting (the brown, aquamarine and pinkish arabesques, also the colorful area, middle right edge). But then our apartment management decided at short notice to clean out asbestos from the basement storage rooms. Dark damp cages where we had stored much stuff, including our daughters' delightful drawings made as children. Saving the drawings from the mold and obscurity is quite different from how Orpheus of myth rescued his bride Eurydice from the underworld. But to my heat-addled brain, listening to Monteverdi's opera L'Orfeo (and watching a video of the performance even as I worked on the central portion of the painting), the two tasks did not seem that different. I listened to L'Orfeo five times while I struggled to paint the lovers' images, erasing and repainting repeatedly. Incidentally, a decade earlier I had painted a silver panel also devoted to Orpheus in the Stravinsky painting of this series. The other operas came easier: Il Ritorno d'Ulysse in Patria (blue, bottom) and L'Incoronozione di Poppea the opera about Poppea's ambitious love for Nero (orange areas bottom left). Also a Mass for six voices In illo tempore (orange bottom right), and the Magnificat, the Virgin Mary's song of praise from the Vespers (dark aquamarine, top right). |

|

[49] Mariam Tamari can be heard singing Violon and other songs at http://mariamtamari.blogspot.com |